Housing Affordability: Policy Promises vs. Market Reality

Housing affordability has become one of the defining economic challenges of our time. Home prices remain elevated, inventory is tight in many markets, and higher mortgage rates have pushed monthly payments well beyond what many households can reasonably afford.

Recently, two housing-related policy ideas associated with Donald Trump have entered the national conversation:

- A proposal for the government to purchase $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities to help push mortgage rates lower

- A proposal to block large institutional investors from purchasing single-family homes

Both are framed as solutions to housing affordability. One of them—restricting institutional investors—is, in my view, a good policy direction. But neither proposal, on its own, addresses the core structural issues that have made homeownership increasingly unattainable, especially for first-time buyers.

To understand why, we need to look beyond headlines and into the realities of the housing market.

Mortgage Bond Purchases: Helpful, but Limited

The first proposal involves government-backed entities purchasing large volumes of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in an effort to lower mortgage rates.

How This Works

Mortgage-backed securities are bundles of home loans sold to investors. When demand for these securities rises:

- Prices increase

- Yields fall

- Mortgage lenders can often offer slightly lower interest rates

This approach has been used before, including during periods of quantitative easing.

What It Likely Accomplishes

Most analysts estimate that a $200 billion MBS purchase could:

- Reduce mortgage rates by roughly 0.10%–0.20%

- Modestly improve monthly payments

- Offer short-term relief, depending on broader bond market conditions

Lower rates help at the margins, but they don’t fundamentally reset affordability—especially when home prices remain historically high. There’s also a tradeoff: lower rates can increase buyer demand, which in supply-constrained markets can push prices higher and offset some of the benefit.

Blocking Institutional Investors: A Good Move, With Realistic Expectations

The proposal to block large institutional investors from buying single-family homes is directionally positive. It addresses fairness and competition, particularly in markets where large investors can outbid individual buyers with cash.

That said, the scale of institutional ownership is often misunderstood.

How Much Housing Do Institutions Actually Own?

Nationally:

- Large institutional investors own roughly 1–3% of all single-family homes

- That equates to approximately 300,000–500,000 homes out of more than 80 million single-family homes nationwide

Institutional ownership is real—but relatively small at the national level.

If we’re serious about addressing the impact of institutional investors, limiting future purchases alone isn’t enough. Institutional investors already own hundreds of thousands of single-family homes, and stopping new acquisitions does nothing to increase current housing supply. A more meaningful approach would involve a slow, orderly liquidation of existing institutional holdings over time to help return inventory to the market—particularly in investor-heavy regions.

Where It Matters More

Institutional ownership is highly concentrated in certain metro areas, particularly parts of the Southeast and Sun Belt. In those markets, restricting institutional purchases could meaningfully reduce competition for individual buyers. Nationally, however, the impact on prices would likely be limited.

Quick clarification: neither of these proposals is currently law. The mortgage-bond idea is being explored administratively, while any restriction on institutional buyers would require new legislation from Congress and formal rule-making before it could take effect. For now, these should be viewed as policy signals, not guaranteed or immediate changes.

The Overlooked Reality: Most Investors Aren’t Institutions

A crucial nuance in the affordability debate is the difference between institutional investors and small landlords.

- Roughly 15–20% of single-family homes in the U.S. are investor-owned

- The vast majority of those homes—approximately 13–15 million properties—are owned by mom-and-pop investors, typically individuals or families owning fewer than 10 homes

- Large institutional investors account for only a small fraction of total investor ownership

Blocking institutional investors does not remove most investors from the market, nor does it suddenly flood the market with inventory.

The Real Affordability Crisis (And Why First-Time Buyers Are Now Nearly 40)

While policy discussions often focus on rates and investors, the true affordability crisis is driven by long-term structural forces.

One statistic captures the severity of the problem:

The average first-time homebuyer is now roughly 38–40 years old, compared to the early 30s just a few decades ago.

That shift isn’t cultural—it’s economic.

1. Home Prices Have Outpaced Wages

Home prices have risen two to three times faster than incomes over the past several decades. Low interest rates in the 2010s masked this imbalance, but once rates rose, the underlying problem became impossible to ignore.

2. Down Payments Are the Primary Barrier

For many buyers, the issue isn’t the monthly payment—it’s the upfront cash:

- Rising prices inflated required down payments

- Rent inflation eroded saving capacity

- Saving tens of thousands of dollars while paying rent has become increasingly unrealistic

3. Student Debt and Delayed Life Milestones

Student loans reduce borrowing capacity, increase debt-to-income ratios, and delay marriage and household formation. Buyers are entering the market later—and often at a disadvantage.

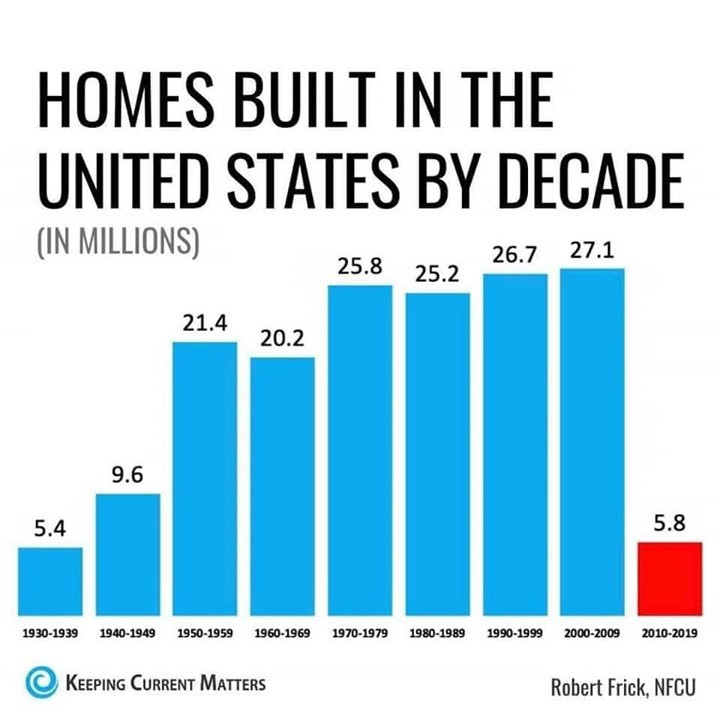

4. A Decade of Underbuilding

Following the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. spent more than a decade underbuilding housing:

- Millions of homes were never constructed

- Builders shifted away from entry-level housing

- Starter homes largely disappeared in many markets

This supply shortage is arguably the single biggest driver of today’s affordability crisis.

5. Zoning and Regulatory Constraints

Local zoning and land-use rules limit density and housing diversity, especially in high-demand areas. Even where demand is strong, supply cannot respond quickly or affordably due to regulatory friction.

Looking Ahead: Interest Rates and Affordability

As we continue through the year, most forecasts suggest mortgage rates will likely remain near current levels, around the low-6% range, with modest declines possible if inflation cools and bond yields fall.

- A small rate decline (0.25%–0.50%) can help some buyers qualify and slightly reduce payments

- If rates stay flat, affordability challenges persist

- A sharper decline into the 5% range would meaningfully improve affordability—but would likely require broader economic shifts

Even in the best-case scenario, lower rates alone won’t solve affordability if housing supply remains constrained.

Bottom Line

Blocking institutional investors from buying single-family homes is a good policy direction, and modestly lower mortgage rates can help at the margins. But neither approach solves the core affordability problem.

The reason the average first-time buyer is now approaching 40 isn’t because of one bad actor or one missing policy—it’s because the system increasingly requires more time, more capital, and more stability than it used to.

Real, lasting affordability will only improve when:

- Housing supply increases at attainable price points

- Zoning and land-use policies allow flexibility

- Entry-level and workforce housing return at scale

Until then, affordability pressures will persist—regardless of rate tweaks or policy headlines.

Elevate Your Career

Learn how you can thrive in our brokerage. Contact us for more info!

More from the Advisor Journal

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.